Patterns of representation in the European Committee of the Regions

The European Committee of the Regions (CoR) is often ascribed a dual role: first, as a guardian of regional interests at the European level, and second, as a link between the EU and its citizens to strengthen the Union’s democratic legitimacy. In his blog post, Gunnar Placzek illustrates how these attributions correspond to the actual composition of the CoR by mapping out patterns of representation.

Since its creation in 1994, the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) has been the main institution for European regions and local authorities to represent their opinions and interests at European level. In addition to influencing the EU legislative process as an advisory institution to the Commission, Parliament and Council of the EU, the CoR also regards itself as a link between the EU and its citizens. As stated in its main principles, the Committee seeks “to bring EU citizens closer to the EU. By involving regional and local representatives who are in daily contact with their electorate’s concerns […], the CoR contributes to reducing the gap between the EU institutions’ work and EU citizens”.

This self-description is in line with the justification for the strengthening of the CoR in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007: The reform was part of a larger effort to increase the EU’s democratic legitimacy by shifting decision-making power in the EU from executive bodies and technocrats to parliaments and elected representatives.

But to what extent does a strengthening of the CoR contribute to the more general aim of strengthening parliamentary representation in EU decision-making? To answer this question, it is helpful to look more closely at the CoR’s exact composition. Since all 27 member states can set their own rules for the formation of their national delegations, the committee is a highly diverse institution and conclusions about its collective actions need to be drawn with care. The REGIOPARL research project has therefore created a database of all CoR members as part of its broader data collection for the interactive European Regional Democracy Map.

Utilizing newly collected data

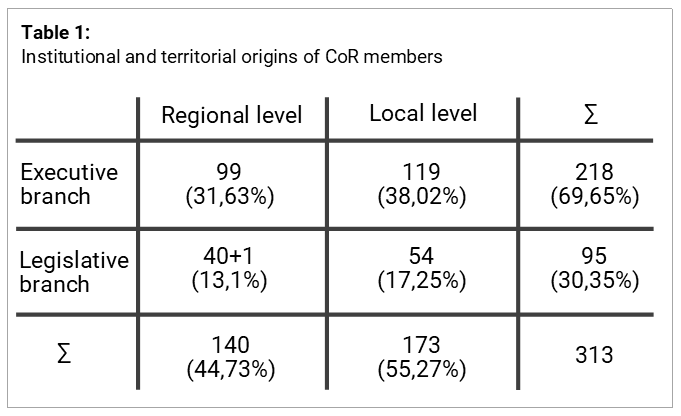

The database currently consists of 313 CoR members.[1] It encompasses all representatives’ names, regions of origin, institutional origins (regional or local level, executive or legislative branch) as well as their respective EU party groups, thus allowing us to map out patterns of representation within the CoR.

Overall, the data show that there is roughly equal representation of members from regional (45%) and local (55%) institutions in the CoR (see table 1). In contrast, the executive dominance that prevails in the EU in general is mirrored in the committee as well: Only 30% of all members derive from a legislative body.[2] Particularly striking is the number of only 40 regional MPs – plus one former governor appointed by a regional assembly – in the CoR, which corresponds to just above 13%. In fact, there are almost twice as many mayors (79) in the committee as there are regional parliamentarians.

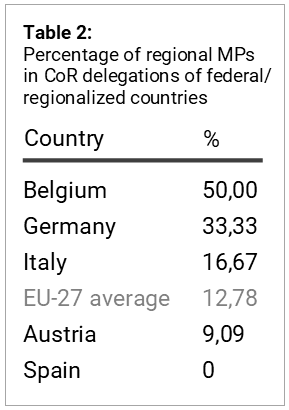

One might expect that representation of regional MPs in CoR delegations is higher for member states with domestically stronger regional parliaments, namely federal or regionalized states like Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Their regional parliaments hold significant powers in domestic politics, can pass their own regional laws and are therefore also involved in the Early Warning System of subsidiarity control according to the Treaty of Lisbon. This status can be assumed to be reflected in a strong representation in the CoR. Surprisingly, however, this is not consistently the case. While Belgium and Germany indeed display higher numbers of regional MPs in their delegations, Italy ranks just above the EU-27 average (see table 2). On the other hand, Spain does not appoint any regional MPs to the CoR, and in Austria only one region (Salzburg) sends a delegate nominated by the regional parliament – who is, however, a former governor. The Spanish and Austrian CoR delegations are clearly dominated by the regional executive, including many governors and regional ministers.

Contrarily, there are other states that deploy a remarkably large number of regional MPs to the CoR, although regional parliaments do not play a very prominent role domestically, such as Hungary (50%) and Sweden (33%). Consequently, the domestic powers of regional parliaments appear not to play as significant a role in the composition of national delegations as one might expect.

Guardian of executive interests?

Despite lacking a formal veto power in the EU’s legislative process, the CoR has established itself as a very important institution to voice regional and local interests at the European level. A recent example of its impact is the involvement of regions and coastal communities in decisions on the distribution of the Brexit Adjustment Reserve (a program to help mitigate the economic consequences of Brexit in the communities most affected), which the CoR had pushed for. Its diversity certainly counts as one of the committee’s main strengths. Joining multiple perspectives of mayors, city councilors, regional MPs, ministers, and governors from all across the EU guarantees that truly all those voices responsible for implementing EU policies on the ground are heard in Brussels.

The continuation of EU executive dominance in the composition of the CoR with only 30% of its members representing a directly elected assembly can be interpreted in different ways. On the one hand, it might be seen as a further indication of disadvantaged legislative actors within EU structures and processes. On the other hand, it may also point to the importance that regions attach to the CoR: By sending their governors or regional ministers as delegates to the CoR, regions signal that this institution is of vital importance to them, therefore seeking for participation at the highest level.

It would be interesting to see whether the institutional background (i.e. regional executives or legislatures) does make a difference regarding delegates’ capacities for successfully promoting regional interests as part of the CoR’s efforts vis-à-vis the European Commission and other EU institutions: Do CoR resolutions primarily highlight challenges faced by regional or local executives implementing EU legislation on the ground? Or does the committee specifically pick up on impulses and interests from constituencies to actually bring the EU closer to its citizens, as it has set out to do? Addressing these questions could be subject to future research on the CoR and its activities and members.

[1] The missing members to the official CoR size of 329 members result from temporarily incomplete national delegations. Because regional or local elections are held regularly across the EU, which in turn condition nominations to the CoR, the committee is almost never fully composed. As of 20 May 2022, the cutoff date for our dataset, only 18 of 27 national delegations were complete. Furthermore, one French CoR member was excluded from the dataset for representing one of France’s overseas territories which are not displayed in the European Regional Democracy Map.

[2] We define legislative bodies as directly elected assemblies at the regional or local level. It should be noted that this definition does not always match the legal definition of the member states. In Germany, for example, municipal councils formally count as part of the executive branch, but for the purpose of our data collection we have classified them as legislative institutions in their capacity as directly elected assemblies.