The future of regional parliaments in the EU: two different perspectives on their role for European democracy

In der Europäischen Union existiert eine Vielzahl an subnationalen Parlamenten, auf lokaler, kommunaler oder regionaler Ebene. Einer bestimmten Gruppe ist in den letzten zehn Jahren zunehmende Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt worden: Regionalparlamente mit eigenen Gesetzgebungskompetenzen. Die Stärkung der Rolle dieser Parlamente im politischen Mehrebenensystem der EU ist mit der Hoffnung bzw. dem Anspruch verbunden, die demokratische Legitimität der EU zu verbessern. Der folgende Beitrag schlägt vor, zwischen einer ‘europäische Demokratie-erweiternden’ und einer ‘Autonomie-erhaltenden’ Perspektive auf die Rolle der Regionalparlamente zu unterscheiden. Die Unterscheidung der zugrundeligenden, normativen Annahmen dieser beiden Perspektiven macht auf mindestens zwei grungrundsätzliche Probleme in der wissenschaftlichen und politischen Debatte aufmerksam. Ein Problem betrifft die Vereinbarkeit der Stärkung von Regionalparlamenten mit der Stärkung der europäischen Mehrebenen-Demokratie. Das andere Problem betrifft den ausschließlichen Fokus auf Regionalparlamente mit (verfassungsmäßig garantierten) Gesetzgebungsbefugnissen. (Beitrag in englischer Sprache)

————————————————————————————————————

The variety of parliaments in the EU

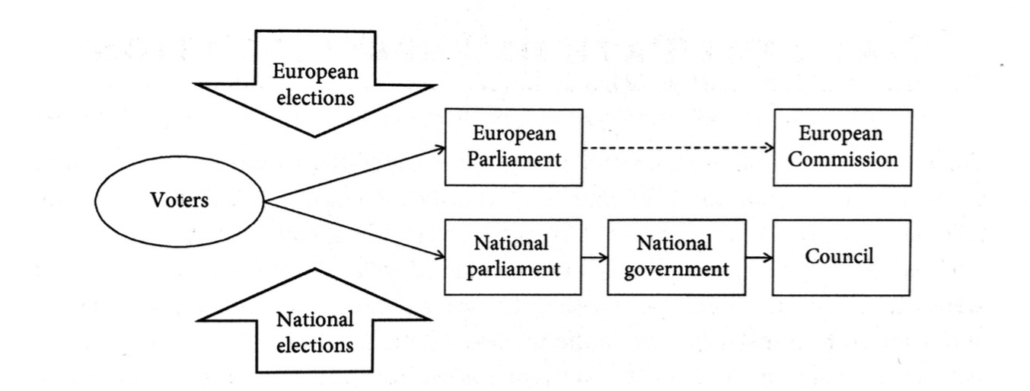

Since its founding in the 1950s, the European Union developed a unique model of political legitimation that combines two paths of democratic representation. Its basic structure is similar to a federal state with one path representing the constituent (member) states in the Council of Ministers (Council) and the other path representing European citizens directly in the European parliament (EP).

Figure adopted from Hobolt 2020, 623

Both channels depend on electoral representation, with Members of the European Parliament being directly elected and national representatives in the Council being indirectly elected by European citizens. Accordingly, two types of parliaments bear the EU’s dual system of democratic representation: the supranational European Parliament and national parliaments who control their governments’ legislative actions in the Council. Thus, in the EU, parliaments from different levels are involved in what scholars have called ‘compounded representation’ (Benz 2003) in a ‘multi-level political system’ (Hix 2007).

The dual structure of representation tends to hide the fact that there are many more active parliaments comprised in this system apart from the supranational and national level. Subnational assemblies are numerous and most of them date back way longer than their national counterparts. Take the Hamburger Bürgerschaft: the legislative assembly of the independent German city-state of Hamburg dates back to the 15th century when bourgeois representatives organized to control the city council. In the same period, Polish sejmiks formed as regional assemblies of the Polish estate (Stone 2001, 77); revived in the administrative reforms in the 1990s, voivodeship sejmiks currently constitute Poland’s 16 regionally elected parliaments.

Regional parliaments with legislative competences in the EU’s multi-level democracy

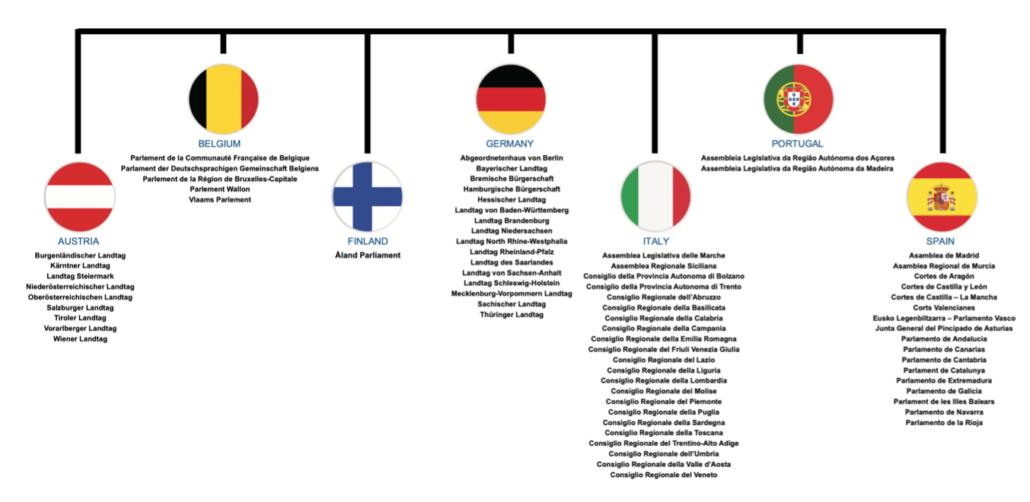

These parliaments are located at the local, municipal or regional level and rather heterogenous regarding their competences and institutional structures – see Loughlin/Hendriks/Lidström 2011 for a detailed overview.[1] One specific group has received increasing attention in EU studies over the last decade: regional parliaments with own legislative competences – of which there are roughly 70 in seven EU member states as of today.[2]

Table of regional parliaments with legislative powers, adapted from CALRE

The renewed interest in these institutions came in the wake of the Treaty of Lisbon, which introduced the so-called Early Warning System (EWS): a process by which the national parliaments of EU member states have the opportunity to oppose legislative proposals by the European Commission on the basis of subsidiarity concerns. The implementation of this prerogative has, for the first time, also incorporated regional parliaments in the EU’s constitutional framework: applying the EWS as a tool of subsidiarity control,[3] national parliaments or chambers of EU member states are now expected to ‘consult, where appropriate, regional parliaments with legislative powers’ (TEU, Protocol 2, Art. 6).

When the Lisbon Treaty is thus seen as having opened a window of opportunity for these regional parliaments to develop capacities and a discrete role in EU politics, one prevailing issue is their potential to improve multilevel European democracy. Indeed, regarding the basic question why regional parliaments should play a role in EU affairs, ‘the predominant answer given … was that regional parliamentary involvement improved the overall democratic legitimacy of the EU’ (Abels in CoR 2014, 2).

Regarding this underlying motive, it is crucial to distinguish two perspectives on the democratic role of regional parliaments with legislative powers – two perspectives that bear on rather different lines of normative argument, which tend to blur in discussions on the future of these institutions in the EU.

Two perspectives on the democratic role of regional parliaments with legislative powers

One perspective emanates from the perception of regional parliaments as ‘losers of European integration’ – in the sense that their more or less autonomous power is being curtailed by the transfer of legislative competences to the European level. The safeguarding of subsidiarity is thus a tool to ensure the (constitutional) rights of autonomous regions. And for the sake of democratic legitimacy, their legislative assemblies should be involved in this process. We can call this the autonomy-preserving perspective on the democratic role of regional parliaments: strengthening regional parliaments in EU policy making for the purpose of guarding regional democracy ‘at home’.

The second perspective emanates from the discourse on the EU’s ‘democratic deficit’ or ‘disconnect’. The deficit claim, broadly speaking, describes the much debated problem that the process of EU public policy making falls short of being an expression of government of and by the people – such that EU decision making would be responsive to a genuinely democratic process of public will formation on European issues.[4] From this perspective, the further involvement of regional parliaments in the EU’s multi-level political system should improve the democratic quality of the latter on the grounds of a set of particular qualities of these parliaments. Since, for example, ‘subnational parliaments are closer to citizens and their problems’ and could ‘improve feedback loops involving citizen attitudes towards EU politics’ (Abels 2015, 42), they would enhance the democratic functioning of the EU policy cycle. We can call this the European democracy-extending perspective on the role of regional parliaments: their parliamentary functions complement or supplement the overall multi-level political system of the EU by improving its democratic quality.

Sure enough, these two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Subsidiarity and democracy can be complementary in several respects. Especially the federalist perspective argues in favor of such a connection (Benz 2020, 70–80) and regional political actors such as the Committee of the Regions deploy the subsidiarity principle as the ‘yardstick for assessing the democratic legitimacy of EU legislation’ (CoR 2013, 10).[5]

The notion that the two perspectives are really two sides of the same coin corresponds to institutional interest of the select group of regional parliaments with autonomous legislative powers in the EU – especially the powerful German Länder parliaments assume a leading role in advocating for the strengthening of regional parliaments, which is a matter that flies better if it is connected to the prospect of improving the democratic credentials of EU public policy making. But it is important to recognize the different nature of the underlying assumptions of the two perspectives for at least two key reasons.

1 Protecting subsidiarity vs. extending multi-level democracy?

First, the two perspectives can come into conflict: the politics and reforms that strengthen the role of regional parliaments in EU affairs could be conducive to regional democracy from the autonomy-preserving perspective but undesirable from the European democracy-extending perspective – by actually being detrimental to the democratic functioning of the EU multi-level system as a whole. Take the example of ‘a binding mandate for regional parliaments so they could monitor their governments more effectively’ in EU affairs (Ries in CoR 2014, 4). From the autonomy-preserving perspective, this proposal has a natural appeal since it promises to compensate for (some) legislative authority and influence that regional parliaments lost in the wake of EU integration. But from the European democracy-extending perspective, such a reform could be running the risk of creating relationships of ‘strict coupling’ (Benz 2003, 90) that actually hamper effective policy making in the overall system.

Furthermore, in ‘defending’ regional democracy in the EU, the autonomy-preserving perspective is principally concerned with the ‘government focused’ type of parliamentary functions such as scrutinizing executive actors via parliamentary committees. This focus is reflected in scholarly work, which barely engages with the ‘representation focused’ functions of regional parliaments with legislative powers, in the context of EU affairs – such as communication with the (regional) constituency or public debate on European issues. The autonomy-preserving perspective is prone to disregard the question of whether or not these parliaments actually do or may exhibit representative qualities that could benefit EU multi-level democracy: qualities often casually referred to as regional ‘closeness to citizens’, where regional parliaments could tap into a special regional ‘allegiance of their citizens’ (Piattoni 2019, 21) and thus make a distinct, meaningful contribution to multilevel parliamentarism in the EU.

2 ‘Constituionally secured’ autonomy vs. peculiar democratic qualities?

The last observation, regarding ‘representation focused’ parliamentary functions, bears on the second reason to recognize the different rationales of the two perspectives. Taken seriously, the European democracy-extending perspective would stress a set of parliamentary functions and qualities that may not be peculiar to the select group of regional parliaments with legislative competences – potentially undermining their claim to a special status in the debate.

When the argument in favor of strengthening the role of regional parliaments in the EU is based on their special representative qualities, such as ‘closeness to citizens’, then it seems reasonable to consider also subnational parliaments without autonomous legislative powers – which are not included in the EWS prerogative. Put in general terms: the autonomy-preserving and the European democracy-extending perspective may not only conflict with each other but they may also fall apart.

The latter case is illustrated by Gabriele Abels’ view that ‘where regional structures exist and are constitutionally secured, where regional identities are strong and involved in one way or another in EU affairs, the regional level will and should play at least a complementary role’, which ‘also requires parliamentary involvement for normative reasons’ (Abels 2015, 45). The first and the second premise of her argument, however, can fall apart: the salience of EU affairs in regional politics or the ability of regional parliaments to represent ‘regional interests and concerns’ (Auel/Hüttmann 2015, 347) is conceptually and empirically independent of the constitutionally guaranteed autonomy of regional parliaments with legislative powers – which is not to say that the premises cannot go together.

Thus, if we would find that representative qualities like regional ‘closeness to citizens’ are not peculiar to the select group of regional parliaments with legislative competences, then we may come to discard the autonomy-preserving perspective with its particular focus: what about the role of other subnational assemblies such as the French conseils régionaux on the grounds of extending European democracy to the regional and more generally the subnational level? Notwithstanding the (political) feasibility of such considerations, the example illustrates a general point: several democracy-based arguments that are made in favor of including regional parliaments with legislative powers actually work independently of the special (constitutional) claim of these institutions.

In conclusion, the two perspectives on the debate on the democratic role of regional parliaments with legislative powers demonstrate at least that: 1) strengthening the ‘government focused’, controlling functions of these institutions in the EU multi-level system may actually hamper the democratic functioning of the latter, 2) taking seriously the alleged peculiar democratic qualities of regional parliaments might support politics and reforms that would not be confined to those parliaments that make up the select group of regional assemblies with own legislative powers – possibly weakening their special standing in the debate.

—

[1] It is controversial among political scientists which of these assemblies (Volksvertretungen) should be termed as ‘parliaments’. For the view that, for example, French regional councils are not to be understood as such see Auel 2002, for the opposing view see Höpcke 2014.

[2] The number varies in different studies/assessments, depending i.a. on whether Italy accounts for 20 or 22 regional parliaments – compare e.g. CoR 2011, 9 (fn 24). With Brexit, the regional assemblies of Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland dropped out of the count.

[3] The EWM is spelled out in Article 4 of TEU Protocol 2, which elaborates the Treaties’ general clause on subsidiarity: that the EU shall refrain from pursuing public policy objectives that can be ‘sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at central level or at regional and local level’ (TEU, Art. 5.3).

[4] For an overview and helpful analysis of the different aspects of the democracy deficit see Hurrelmann/Debardeleben 2009.

[5] Quoted after Abels 2015, 35.

References

Abels, G. 2015, Subnational parliaments as ‘latecomers’ in the EU multi-level parliamentary system – introduction. In G. Abels and A. Eppler (eds.), Subnational parliaments in the EU multi-level parliamentary system: taking stock of the post-Lisbon era. Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 23–60.

Auel, K. 2002, Akteure oder nur Statisten? Regionale Parlamente im Europäischen Mehrebenensystem. In T. Conzelmann and M. Knodt (eds.), Regionales Europa – Europäisierte Regionen. Frankfurt; New York: Campus, 191–212.

Auel, K. and Hüttmann, B. 2015, A life in the shadow? Regional parliaments in the EU. In G. Abels and A. Eppler (eds.), Subnational parliaments in the EU multi-level parliamentary system: taking stock of the post-Lisbon era. Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 345–356.

Benz, A. 2003, Compounded representation in EU multi‐level governance. In B. Kohler-Koch (ed.) Linking EU and national governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 82–110.

—, 2020, Föderale Demokratie. Regieren im Spannungsfeld von Interdependenz und Autonomie. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

CoR (Committee of the Regions) 2011, The subsidiarity early warning system of the Lisbon Treaty – the role of regional parliaments with legislative powers and other subnational authorities (Report). Brussels: https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/subsidiarity-warning-system-lisbon-treaty.pdf

—, 2013, Subsidiarity annual report 2013. Brussels (retrieved 7 JAN 2015, quoted after Abels 2015).

—, 2014, Strengthening the role of regional parliaments – challenges, practices, and perspectives. (Proceedings). Brussels.

Hix, S. 2007, The EU as a new political system. In D. Caramani (ed.) Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 573–601.

Hobolt, S. 2020, Representation in the European Union. In R. Rohrschneider and J. Thomassen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of political representation in liberal democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 621–636.

Hurrelmann, A. and Debardeleben, J. 2009, Democratic dilemmas in EU multilevel governance: untangling the Gordian knot. European Political Science Review 1(2), 229–247.

Loughlin, J., Hendriks, F. and Lidström, A. 2011, The Oxford Handbook of local and regional democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piattoni, S. 2019, The contribution of regions to EU democracy. In G. Abels and J. Battke (eds.) Regional governance in the EU. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 16–32.

Stone, D. 2001, The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. Seattle; London: University of Washington Press.

TEU (The Treaty on European Union), consolidated version 2016. Official Journal of the European Union 12016E/TXT: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12016E/TXT&qid=1617368427819&from=EN